This article has two parts. The first examines some of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers; the second part looks at the book by John Climacus, The Divine Ladder.

Part 1: THE DESERT FATHERS AND MOTHERS: A MODEL FOR CHRISTIANS?

Brief Background

The core collection of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers (also known as Apophthegmata Patrum) primarily contains sayings from ascetics who lived in the Egyptian, Syrian, and Palestinian deserts in the 4th and 5th centuries. The main alphabetical and systematic collections of the Apophthegmata Patrum were largely compiled around the 5th and early 6th centuries. The book cited in Part 1 is The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Cistercian Publications, 1975, trans. Benedicta Ward.

These sayings and stories come from oral tradition as information relayed by the followers of these desert fathers, especially of Anthony, “father of monks” (xviii). I was unable to find any source that cites evidence that the desert fathers said what they supposedly said or did the things claimed for them. In the case of some with the same name, it is not clear who said what (xxviii, xxix-xxx). The stories are viewed as being “close to parable and folk wisdom” (xix).

These men and women moved into the deserts (Egypt, Syria, Asia Minor, and Palestine) first due to persecution, and later, after Christianity became mandatory under Emperor Theodosius. The desert fathers sought a life of poverty, simplicity, spiritual purity and prayer.

Monasticism was a direct result of the influence of the desert fathers, who lived apart from society, practicing asceticism, silence, and solitude. Later, they formed communities that were the seed for monasteries. Their influence is also found in the Rule of St. Benedict through the writings of John Cassian (360-435) and others, such as Jerome. Cassian founded two monasteries near Marseilles and passed on what he learned from the desert teachings. These writings eventually formed the basis of what is called “the sayings of the desert fathers.” The sayings were rearranged over time, first written in Coptic or Greek (xx).

These practices are what are fueling the Contemplative Movement today. Contemplatives draw from the lifestyle and ideas of the “Fathers,” as well as from the monastic traditions started by St. Benedict, essentially creating the present wave of neo-monasticism in the church. I have run across so many references to the desert fathers and mothers, as well as having received numerous messages and emails from Christians about their pastors or other church leaders citing these desert fathers, that I think it is crucial to examine these areas.

There are numerous works on the history and practices of these desert fathers which can be consulted for more detail. The purpose of this article is not historical, but to examine from a biblical point of view some of the words and actions attributed to the desert fathers; and to look in Part 2 at the work of one of these fathers, John Climacus, The Divine Ladder. I put page numbers by some of the quotes but not all, as it became too time consuming.

Diving In

This book is a reference of sayings from these fathers, called Abbas (the women are called Ammas); it is not narrative or historical. It is divided up alphabetically by name with paragraphs about each desert father or mother, their supposed deeds, and words attributed to them. It immediately reminded me of Buddhist texts I read when I was following Zen Buddhist ideas in the New Age, prior to my faith in Christ.

The Zen writings usually consist of stories of various Buddhist monks centuries ago and things they said to their followers to reveal the truths sought in Buddhism. A difference between this book and the Zen writings is that the Zen teachings make sense in the context of Buddhism, as strange as they sound. However, most of the material in this book does not make sense in the context of a biblical worldview.

The Abbas give moral advice, such as resisting desires of the flesh by harsh treatment of the body, teach to withdraw from society, and recount what might be called allegories or parables to make a point.

I want to make it clear that some of the stories and statements are in harmony with Scripture, such as when one said that the fear of God, “when it penetrates the heart, illumines him, teaching him all the virtues and commandments of God,” (104).

There are many statements urging to turn from vices and sin and to turn to God. However, the redeeming tales and statements are heavily interspersed with the problematic or even disturbing content.

Fantasy-like

From the selections I read in the book, many of the tales are in the realm of fantasy. Below are brief examples. The titles are mine. In some cases I quote the example in its entirety, indicated by quotation marks; in others, I summarize and then quote.

Stones in Mouth

“It was said of Abba Agathon that for three years he lived with a stone in his mouth, until he had learnt to keep silence” (22).

Flies, Demons, and Fire

Abba Bitimius relayed an account from Abba Macarius. This is a longer account involving two strangers who came to live with him. He asked God to show him their “way of life.” He saw demons “like flies” on the younger stranger, some in his mouth and some in his eyes. He saw “the angel of the Lord” chase the demons away with a fiery sword. As the younger man chanted psalms, he saw a “tongue of flame” coming from his mouth and going up to heaven. When the older man changed, it was like “a column of fire” going up to heaven. Abba Marcarius said he learned from this that the older man was “a perfect man” but the younger still had the enemy fighting against him. A few days later, both men died. Abba Marcarius called his cell “the place of martyrdom of the young strangers” (134-36).

Speaking Skull

One account is about Abba Marcarius hearing the skull of a dead man that he found on the ground speak to him. The skull told him that in life he had been a pagan priest and asked Marcarius to pray for the dead who are in torment. Allegedly, the skull said that he and the others stand in fire from foot to head (in hell, presumably) and cannot see each other’s face but only their back. But when people prayed for them, they got a bit of respite by seeing a bit of the faces of the others. (136-37)

What’s the Point?

This section is called “What’s the point?” because these stories or statements seem to have no spiritual merit and/or no useful point, or a point not that insightful or unusual. There are a quite a few of these, some of which remind me of the Zen stories.

Beans

Abba Isaiah cooked some lentils for another monk and brought the lentils to him as soon as they had boiled. The monk said that the beans were not cooked. Abba Isaiah replied, “Is it not enough simply to have seen the fire? That alone is a great consolation.”

Incense Ashes

“It was said of Abba Isaac that he ate the ashes from the incense offering with his bread.”

Strange Pronouncement

A brother visited Abba Ammoes “to ask him for a word.” He stayed with him for seven days, but Abba Ammoes never spoke. Then, when the brother left, Abba Ammoes said, “Go watch yourself; as for me my sins have become a well of darkness between me and God.”

Confusing Theology

There are quite a few tales that give credibility to bad theology (and to ascetism).

The Body and Blood of Christ

There is a longer account given by a monk that comes from another monk (many stories start like this, “Abba X heard a story from Abba Y about Abba Z that….”) about a man who did not believe the teaching that the bread and wine in communion actually become the body and blood of Christ. The monks advised the man to pray, so he did. The monks also prayed for him. Then the two monks went to church on Sunday with the unbelieving man.

When the priest placed the bread on the table, the two monks and the man who went with them saw a little child on the table. As the priest started to break the bread, an angel came down from heaven and poured the child’s blood into the chalice. “When the priest cut the bread into small pieces, the angel also cut the child in pieces.” As they began to take the elements, the man who had not believed in the teaching about the body and blood of Jesus received a “morsel of bloody flesh.” At that moment, the man cried out that he now believed, and the flesh turned into bread. The monks explained that God knows man cannot eat raw human flesh, so he changed it back into bread (53-54).

Asceticism Keeps Away Demons

Abba Isidore was asked why the demons were afraid of him (Isidore). Isidore replied that it was because he had practiced asceticism from the time he became a monk, and did not allow anger to reach his lips.

An Evil Nod

Abba Isaiah said that if someone wishes to give evil for evil, “he can injure his brother’s soul even by a single nod of the head.”

How to be Saved

Abba Biare was asked “what shall I do to be saved?” Biare told him, “Go, reduce your appetite and your manual work, dwell without care in your cell and you will be saved” (44).

Demons

There are many stories containing demons. Some are so bizarre that they made me laugh. The demons are often characterized as though they are little mischievous children. Some of the accounts talk about how the Abbas had verbal spars with demons or were bothered by demons but overcame them.

Making the Monk Laugh

One monk named Abba Pambo was said to never smile. So demons decided to make him laugh by sticking feathers from a wing to a lump of wood. This did make Pambo laugh so the demons pointed this out to him. But he replied that he had not laughed, but rather was making fun of the demons because it took so many of them to carry this stick with feathers (197-98).

Pambo is the same one whom God supposedly glorified so that no one could look at him steadily. His face shone like lightning and he sat like a king on a throne (195-96, 197).

Demon with a Knife

“Another time a demon approached Abba Marcarius with a knife and wanted to cut his foot. But, because of his humility, he [the demon] could not do so, and he said to him, ‘all that you have, we have also; you are distinguished from us only by humility; by that you get the better of us’” (136).

Binding Demons

Abba Theodore bound three demons who tried to enter his cell, one by one. They begged him to let them go because they were afraid of his prayers, so he let them go (78).

Walking on Water and More

These accounts do not fit any category but stand out for being bizarre.

Walking on Water

Abba Bessarian said a prayer and crossed the River Chrysoaros on foot. Later, his disciple asked him how it felt to walk on water and Bessarian allegedly replied, “I felt the water just to my heels, but the rest was dry.” (140)

That one strikes me as a counterfeit to the account of Jesus walking on water as given in Matthew 14 I recall that in the movie “The Craft,” a 1996 underground hit about teen witches, one of the witches walked on water. Although Peter also briefly walks on water in the Matthew story, it is only because Jesus has commanded him to do so. Peter becomes afraid and starts to sink, then is rescued by Jesus who rebukes him for his lack of faith. Nothing in Scripture gives the idea that Christians should be able to miraculously walk on water.

Fanning Angel

In another account, an old man came to see Abba John (known as John the Dwarf) in his cell. He saw Abba John asleep and an angel above him, fanning him. (92)

Throw Your Son Into the River

In one story, a man comes to Abba Sisoes because he wants to be a monk. The Abba finds out the man has a son, then tells him if he wants to become a monk, to throw his son into the river. But then Abba Sisoes sends another monk after the man to prevent him from doing that. The story continues:

“The brother said, ‘Stop, what are you doing?’ But the other said to him, ‘The Abba told me to throw him in.’ So the brother said, ‘But afterwards he said do not throw him in.’ So he left his son and went to find the old man [Abba Sisoes] and he became a monk, tested by obedience.” (214)

The one above is reminiscent of Abraham being told by God to sacrifice Isaac. The biblical account in Genesis 22 is about faith, and is also a foreshadowing of the gospel when God supplies a ram for sacrifice. The story about the Abba and the man with the son is pointless except to supposedly show complete obedience to an Abba. And this is an Abba who gives ridiculous, unbiblical, and conflicting orders, apparently.

Confusing Advice

Many times the advice is confusing, and there are a lot that fall under this category.

What?

Abba Theodore told someone who said he was perishing and needed a word, “I am myself in danger, so what can I say to you?” (76).

Be a Fire?

“Abba Joseph said to Abba Lot, ‘You cannot become a monk unless you become like a consuming fire’” (103).

Okay to Lie?

Abba Alonius also gave advice to another Abba that one should be able to lie. The example he gave was hiding a possible murderer from the judge seeking him because otherwise the man would die. It is better, claimed Alonius, to leave the man’s fate to God (35).

Asceticism

Asceticism, which is deliberately creating discomfort, hunger, or even pain, was a central practice of most of these communities. Syrian monks “went around naked and in chains….eating whatever they found in the woods” (xviii). There were those who lived on top of a pillar. Simeon Stylites (from the Greek word stylos for “pillar”) allegedly lived for 40 years atop a fifty foot column near Antioch (xix).

Here are examples:

“Abba Bessarion said, ‘For fourteen days and nights, I have stood upright in the midst of thorn-bushes, without sleeping.’” (42)

“The same Abba Bessarion said, ‘For fourteen years I have never lain down, but have always slept sitting or standing.’” (42)

Abba John the Dwarf said that “if a man goes about fasting and hungry, the enemies of his soul grow weak.” (86)

Anthony

Anthony (born AD 251), considered the “Father of Monks” is given special attention at the beginning of the book. He heard the account of what Jesus said to the rich man, to sell all he had and give it to the poor,” and decided he had to do this.

“He devoted himself to a life of asceticism” and after guidance from a “recluse,” he went into the desert in 285 to live in complete solitude. He attracted followers and, around 305, he acted as a “spiritual father” to them, then withdrew into solitude five years later. He did visit Alexandria twice, once to support Athanasius against heresy. After his death, the account of his life by Athanasius was “influential in spreading the ideals of monasticism throughout the Christian world” (1).

Anthony called the monks to renounce the worldly life and to asceticism. He reportedly said,

“suffer hunger, thirst, nakedness, be watchful and sorrowful; weep, and groan in your heart; test yourselves to see if you are worthy of God; despise the flesh, so that you may preserve your souls” (8).

Anthony’s Misunderstanding

Jesus’ advice to the rich man to sell all he had and follow him was not meant for everyone. The point is that Jesus knew the rich man was attached to his wealth and goods and that attachment stood in the way of loving and following Christ. Anything can be that barrier, including renouncing things for the wrong reasons; it is not necessarily wealth.

Worth Reading?

Although many of these accounts offer biblical moral advice, this advice is already found in Scripture. It is not necessary to read the Desert Fathers for any edifying information. Moreover, since this advice is mixed in with these bizarre (and often unbelievable) stories, and since the advice often consists of recommendations to be in silence and solitude, to avoid men, to be harsh on one’s self (asceticism), then what value lies in this book?

Spending time in God’s word, the words inspired by the Holy Spirit, is more edifying and fruitful. Moreover, the principles for Christian living are given clearly to the church in the epistles and do not match many of the behaviors extolled in the Sayings. For new believers, unbelievers, or immature believers not grounded in Scripture, this book could be a spiritual disaster.

It is lamentable that Contemplatives recommend and refer to this book and to the desert fathers and mothers so frequently. What these abbas and ammas said, or reportedly said (since there is little to no verification of it) is not much more valuable than secular moral fables.

Part 2: THE DIVINE LADDER: YOU COULD FALL OFF

John Climacus and the Ladder

One of the main practices of those in the desert and later by monks was extreme asceticism, which involved remaining celibate as well as abuse of the body through not eating, not drinking liquids, and sometimes even harsh beatings of the body.

John Climacus (570-649 AD) is a significant figure in the tradition of the Desert Fathers and Mothers. He lived in the Egyptian desert first with a community of monks, and later in solitude for 40 years. He authored a book on the supposed wisdom of the Desert Fathers and on asceticism, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which became a guide for monasteries, especially in the Orthodox churches, so Climacus is also known as “Saint John of the Ladder.” This is a guide on attaining spiritual perfection.

“The Ladder of Divine Ascent is an ascetical treatise on avoiding vice and practicing virtue so that at the end, salvation can be obtained. Written by Saint John Climacus initially for monastics, it has become one of the most highly influential and important works used by the Church as far as guiding the faithful to a God-centered life, second only to Holy Scripture.

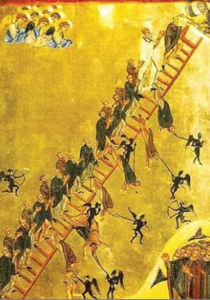

There is also a related icon known by the same title. It depicts many people climbing a ladder; at the top is Jesus Christ, prepared to receive the climbers into Heaven. Also shown are angels helping the climbers, and demons attempting to shoot with arrows or drag down the climbers, no matter how high up the ladder they may be. Most versions of the icon show at least one person falling.” From Orthodox Wiki

There are famous paintings of this ladder, showing monks clinging desperately to the ladder as demons try to knock them off. The ladder is viewed as a metaphor for the need to climb a ladder via certain practices, including asceticism. The Orthodox churches believe in using this book as a guide during the Lenten season. Page numbers given are from The Ladder of Divine Ascent (1982, the Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle, NY; Harper & Harper, 1959, NY, NY).

The book gives 30 steps, and each point under each step is numbered. These steps give spiritual and moral advice or make proverbial statements that cover everything including sleep, solitude, gluttony, purity, prayer, angels, demons, money, pride, the monk community, and more.

Ascetism and The Ladder

It seems one of the major misunderstandings of John Climacus and the other monks in the desert is to view the body as an evil or hindrance to spiritual life. There are many statements in both The Sayings of the Desert Fathers and in Climacus’ Ladder book that show this.

Climacus writes that the flesh is impure and that Paul called the flesh “death” (89) and references Rom. 7:24, but that verse must be read in context of the passage and in the context of other writings of Paul and of the New Testament. Paul is referring to the sin nature and his natural tendency to sin.

Climacus writes approvingly of penitents standing on their feet to avoid sleep; people praying with their hands tied behind their backs, bent to the earth; some were striking their foreheads on the earth; others were “continually beating their breasts;” and there are more instances (48).

“Be malicious and spiteful against the demons and at constant enmity with your body. The flesh is a headstrong and treacherous friend. The more you care for it, the more it injures you” (73).

“Those who aim at ascending with the body to heaven, need violence indeed and constant suffering…” (9).

Climacus references Matt. 11:12 for this statement. The meaning of this verse is debated, but it has nothing to do with Climacus’ assertion.

This view about the body, which is Neoplatonic or Gnostic in nature, permeated the views of the monks in the desert (and to a certain extent monks in later times). They therefore would cause deliberate pain or suffering to their bodies by not eating, not sleeping, or even injuring themselves.

Tales Hard to Believe

Like the Desert Fathers book, there are tales that are hard to believe.

Fragrant Feet

One is about a monk named Menas in a monastery where Climacus was living. Menas died and the third day after his death, there was a fragrance from his coffin. They opened the coffin and “we all saw that fragrant myrrh was flowing like two fountains from his precious feet,” (31).

The Talking Dead

Another story recounts a tale Climacus heard from another monk about a monk named Acacius whose teacher abused and beat him so that he had black eyes and scars. He died after nine years and when the teacher was told, he did not believe it, so he was taken to Acacius’ tomb. He asked Acacius in the tomb if he was really dead, and Acacius answered! This caused the teacher to feel terror and he ended up living in a cell near the tomb admitting he was a murderer.

This story recounts not only a dead man speaking but also physical abuse which apparently is not remarked on.

The Jesus Prayer

John Climacus is credited with starting what is called the Jesus Prayer, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

“Another Desert Father, John Climacus, established a method based on this idea, involving the constant repetition of a single word or short phrase which would help to drop below the chatter of the mind to the open receptivity of the heart. This method influenced what became known as the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me”, described in the 19thC Russian spiritual classic, The Way of the Pilgrim. It was also an inspiration for the Benedictine, Fr John Main in the 20th century, who having learned mantra meditation from Hindu scholar Swami Satyananda in India, was heartened to discover something similar in the Christian practices of the Desert Fathers and Mothers. Fr Main went on to formulate Christian Meditation, employing a similar technique of repetition of a sacred word, a technique which continues to grow in popularity in our own time.” (Source)

Please note that John Main (1926-1982) learned mantra meditation from a Hindu (similar to the use of Hindu and Buddhist meditation methods in the Centering Prayer movement started by Thomas Keating, Basil Pennington, and William Meninger ). The Jesus Prayer is practiced in the Eastern Orthodox churches but has migrated into evangelical churches through the spread of Contemplative Spirituality, including in the practice of Lectio Divina.

Repeating the Jesus Prayer is said to be praying unceasingly, as commanded in a passage in First Thessalonians 5. However, woodenly repeating a prayer is not what this verse is talking about. The verse is about a prayerful attitude and seeking God in all matters. (See this brief video).

Solitude

Living in solitude was considered by the desert fathers and by John Climacus to be the best way (and they often imply the only way) to be close to God and become more spiritual. This is why they sought the desert and usually lived alone.

What is called the practice of solitude has become a chief teaching today among Contemplatives such as Richard Foster, John Mark Comer, Ruth Haley Barton, Tim Mackie, the late Thomas Keating, and others. Silence is often seen as a natural result of and companion practice to solitude, and is heavily extolled as well.

In the Ladder, Climacus devotes Step 27 to solitude. There are online audios which read these steps, such as this one or this one where you can read this Step for yourself, as well as the whole book (the Steps are called “Chapters” on the menu but then listed as “parts” when you click on it).

“A monk living with another monk is not saved as a solitary monk would be. When a monk is alone he has need of great vigilance and of an unwandering mind. When not alone, the other often helps his brother; but an angel assists the solitary.”

“ Those whose mind has learned true prayer converse with the Lord face to face, as if speaking into the ear of the Emperor. Those who make vocal prayer fall down before Him as if in the presence of the whole senate. But those who live in the world petition the Emperor amidst the clamour of all the crowds. If you have learned the art of prayer scientifically, you cannot fail to know what I have said.”

“The celestial powers unite with him whose soul is quiet, and dwell lovingly with him. And the opposite to this is obvious.”

“Those who are thoroughly versed in secular philosophy are indeed rare; but I affirm that those who have a divine knowledge of the philosophy of true solitude are still more rare.”

“He who has attained to solitude has penetrated to the very depth of the mysteries, but he would never have descended into the deep unless he had first seen and heard the noise of the waves and the evil spirits, and perhaps even been splashed by these waves. The great Apostle Paul confirms what we have said. If he had not been caught up into Paradise, as into solitude, he could never have heard the unspeakable words. The ear of the solitary will receive from God amazing words. That is why in the book of Job that all-wise man said: ‘Will not my ear receive amazing things from Him?‘”

Biblical Response to Practice of Solitude

The selected statements copied and pasted above on solitude are not based on Scripture, even though references are made to the Bible in some of them.

Solitude is a particular mental and spiritual state for Contemplatives viewed as necessary for connection to God. It should be a regular practice in order to be more spiritual, according to these Contemplative teachers. They do not mean just being alone, but to also attain an interior silence (via certain methods) and to be still. Prayer is often linked to being in solitude.

Biblical Texts Misused

Biblical texts are consistently misused by Contemplatives to promote solitude:

“But you, when you pray, go into your inner room, and when you have shut your door, pray to your Father who is in secret, and your Father who sees what is done in secret will reward you.” (Matt. 6:6)

A simple reading of the previous verses shows us that Matthew 6:6 is a contrast to the picture of the hypocrites in verse 5 who pray publicly to get attention. Jesus is saying in essence not to show off when praying, and to not pray in order to impress God or men.

There is no textual evidence that Jesus was talking about interior silence and withdrawing into one’s self when he said we should go to the inner room, as claimed by some. The inner room was a small room in houses where people could go for private prayer. Jesus is being literal here. (The writer of this article personally heard Thomas Keating give this incorrect teaching; go to section “Enter Keating’s Inner Room”).

Several texts about Jesus going off by himself are cited by Contemplatives.

Except for the reference in John, these passages state Jesus left to pray. That Jesus went to pray alone is not grounds for the practice of solitude. Jesus was always with his disciples and often with crowds who besieged him for healing. It was only natural that he would want to be alone to pray.

What about the John 6 passage?

Jesus went to be alone in John 6 right after he had miraculously fed the 5,000.

Verse 15 then states:

“ So Jesus, knowing that they were going to come and take Him by force to make Him king, withdrew again to the mountain by Himself alone.”

Jesus knew that the crowds wanted him to be king and were going to be violent. But Jesus was on earth to atone for sins, and the crucifixion had not yet happened. So he left to get away from the crowds and be alone. We do not know if he prayed, but it is reasonable to assume he did pray considering what was going on and considering the other passages that tell us he went off by himself to pray.

Thwarting God

John Mark Comer, for example, teaches that solitude is essential for “life with God.” Many Contemplatives teach that unless we have silence and solitude, we cannot hear God or be close to God.

However, there are numerous accounts of God reaching people who are in the midst of very noisy and busy environments such as Gideon, Moses, Jonah, Paul, and others. Is God hampered by a noisy environment, or by your thoughts? If one is restless and distracted, can that keep God from speaking to anyone if he so desires? This is aside from the issue of whether one should expect God to speak to them; this is about the ability of God to speak to whom he wishes at any moment, no matter what the person is doing or where that person may be. Contemplatives would have one believe that God is thwarted by one’s distractions, noise, or busyness.

There is nothing wrong with being alone to contemplate God or the Bible, or to pray. But if one is alone to do these things, it is the Holy Spirit who will assist one to grow closer to God and to grow more Christ-like, not the solitude.

No Biblical Instruction

There is no biblical instruction or basis for the practices of solitude, or of silence and stillness. Several CANA articles have addressed this (such as here, here, here, here, and several listed here.

In every case of all the Contemplative writings I have read and heard, the attempted use of biblical texts to support Contemplative practices has failed because each time the passage is taken out of context, misinterpreted, had another meaning read into it, or is not applicable.

The Bible’s Response to Asceticism

In Colossians, we read:

“These are matters which have, to be sure, the appearance of wisdom in self-made religion and self-abasement and severe treatment of the body, but are of no value against fleshly indulgence.” Col. 2:23

The Greek word translated as “severe” in the above passage is apheidia, meaning neglect and an “unsparing” treatment of the body. Those practicing these harsh methods thought, like the monks, that they could attain some kind of purification of bodily sins and lusts, and even merit for their suffering. But God denounces this as of “no value.”

In First Timothy, speaking on practices of denying marriage and food, Paul writes against this, saying:

But the Spirit explicitly says that in later times some will fall away from the faith, paying attention to deceitful spirits and doctrines of demons, by the hypocrisy of liars, who have been seared in their own conscience, men who forbid marriage and advocate abstaining from foods which God has created to be gratefully shared in by those who believe and know the truth.” 1 Tim. 4:1-3

It is right to be celibate outside of marriage, but in this case, it was being advocated as lifelong because physical relations were viewed as evil by the early Gnostic-type groups, and also it became the rule for monastic living . Commentator Benson writes:

“This false morality was very early introduced into the church, being taught first by the Encratites and Marcionites, and afterward by the Manicheans, who said marriage was the invention of the evil god; and who considered it as sinful to bring creatures into the world to be unhappy, and to be food for death. In process of time the monks embraced celibacy, and represented it as the highest pitch of sanctity. It is a thing universally known, that one of the primary and most essential laws and constitutions of all monks, whether solitary or associated, whether living in deserts or in convents, is the profession of a single life, to abstain from marriage themselves, and to discourage it all they can in others.”

As Paul also writes in First Timothy:

“…for bodily discipline is only of little profit, but godliness is profitable for all things, since it holds promise for the present life and also for the life to come.” 1 Tim. 4:8

Most commentators agree that the “bodily discipline” refers to the harsh austerities being practiced on the body five verses earlier. One cannot have spiritual sanctification through the practices from men. Transformation is by the Holy Spirit, who uses God’s word, prayer, fellowship with other Christians, and worship to mold one more into the image of Christ.

While Jesus called anyone who wanted to follow him to deny self, this is not done with asceticism. Denying self involves putting Christ above self and anything else. It is about voluntary devotion to Christ, not deliberate harsh treatment of one’s self.

Some may cite as support for asceticism the Nazirite vow of the Old Testament or they may refer to Elijah and John the Baptist who lived in harsh conditions as prophets. However, the Nazirite vow was given by God, and Elijah and John were called by God to be prophets and to live in special circumstances according to how God called them to live. They were not trying to practice harsh asceticism to be holy nor did they live based on their own ideas.

Finally, fasting may be viewed by some as asceticism, but it is a voluntary practice (usually in conjunction with prayer in the Old Testament) for a limited time and not to gain merit with God. It is not harsh treatment or self-injury if done biblically. Since it is for a limited time, it does not really fall into the category discussed here which involves more intense and possibly lifelong practices of harsh treatment to the self.

Asceticism is based on efforts by the flesh (the fallen self), not the Spirit. It is not taught in Scripture and is not honoring to God.

RESISTING THE CONTEMPLATIVE PUSH: THE ESOTERIC VS. THE BIBLE

If a pastor or church leader is promoting the desert fathers, the Jesus prayer, John of the Ladder, or any other contemplative source, keep in mind that nothing in Scripture legitimately supports these ideas or practices. In truth, these practices derive from mysticism.

Mysticism is by nature esoteric. That is, it is secretive and not able to be communicated with the mind or words, but must be sought inwardly and experienced, usually through certain practices (forms of meditation that involve putting the mind in neutral, mantras, or other methods). As this article, which supports such ideas, states:

“Esotericism, by contrast, offers a more structured and selective path. It involves the study of mystical texts, sacred correspondences, ritual practice, and symbolic systems. The seeker often progresses through initiatory grades, each unveiling deeper layers of insight. Esotericism asks, ‘What is the hidden order behind the visible world? And how can I align with it?’”

The above describes the belief about “truths” allegedly hidden behind the visible world, the same belief that this writer had for many years in the New Age. So I am quite familiar with this thinking.

Mysticism and its esoteric spirituality are by nature contrary to God and his revelation. God’s word is offered to all, is meant to be read in a normal fashion (not looking for codes or hidden messages), and reflects God’s character. God does not play esoteric games, hide behind enigmas, nor is he a cipher challenging us to unlock ineffable secrets.

Moreover, the practices of the desert fathers were works-based, seeking to gain favor with God for salvation. This denies the clear teaching of Scripture that salvation is through faith alone by grace alone.

The fact that God’s word and character do not support or reflect the desert fathers’ mystical teachings, asceticism, or esoteric methods for reaching him is the significant thing to know and remember.

Short link: https://tinyurl.com/9x3fkt2r